AMD Heats up the Processor Wars With Cooler Chips

BY Justin Torres

LISTEN

After laying dormant for years, Advanced Micro Devices (AMDs) are back with a fresh new round of products to compete against Intel and Nvidia.

Team Blue: Central Processing Champion

The history of central processing units (CPUs) has more or less revolved around Intel. The front runner of microprocessors began its legacy with the 4004 in 1971. It was a 4 bit processor (a max of 640 bytes of memory) and was built for use in a calculator.

Intel’s next breakthrough was the 8086, which was designed between 1976 and 1978. It sported 16 bits for 1MB of max memory, and with its release came the unveiling of the x86 instruction set. This interface enabled software developers to write forward-compatible code that did not need to be re-written each time a new CPU came out.

With the exception of mobile phones, which are primarily ARM based, every processor released by Intel and its competitors supports x86.

Intel then released a multitude of improvements and incremental upgrades under forgettable names, which did not quite catch mainstream interest. That all changed with Pentium: 32 bits with 4GB of usable memory and a moniker that is still being used two decades later.

Intel's current flagship consumer chip series — the i3, i5, and i7 — is in its 7th generation. With each iteration comes a new architecture. By the latest generation, a majority of the CPUs include integrated graphics, which do not require a dedicated video card and a 14nm build process for significant power efficiency.

Today, Intel is in just about everywhere. If you purchased an iMac or Macbook made after 2006, it is using an Intel CPU. A 2015 study by the International Data Corporation claims Intel held a 99.2 percent market share in server processing chips.

Team Green: From Rendering Clouds to Running Them

Thanks to the power of the cloud, big data operations are easier than ever. These complex algorithms and deep machine learning can be bottlenecked and slowed down by the central processor which is designed for more general tasks. Nvidia has an answer that is poised to define the next era of high-performance computing.

A significant milestone for Intel was the 8800 GTX, which was released over 10 years ago. For the first time you could combine the power of two or three cards with scalable link interface (SLI), which resulted in greater performance than any one card could deliver. It also added support for DirectX 10 and OpenGL, improved software interfaces that enabled games to take full advantage of the hardware.

Additionally, the 8800 GTX introduced CUDA and the Tesla microarchitecture. These technologies simplified the work needed to write the software that runs on the graphics processing unit (GPU). Developers could easily offload their jobs from the CPU and run complex, parallel applications on a dedicated processor without slowing down the rest of the computer.

Nvidia continued to make gaming and workstation graphics cards, which specialized in speed and reliability, respectively. In a recent announcement, however, Nvidia provided a glimpse of the future of cloud computing with the Volta, with a record breaking 21 billion transistors, 16GB of high bandwidth memory and a 5x improvement handling artificial intelligence applications.

When properly utilized, a single GPU-accelerated server can deliver the performance of half a server rack of CPU only servers. Not only does it offer high density and low operating costs for the next generation of cloud computations, a significant percent of high-performance cloud computing software is already compatible with the new architecture.

On the day Nvidia introduced the Volta, it added the entire market cap of AMD plus $2 billion, to their own market cap.

AMD did not just have a response ready, it changed the conversation.

Team Red: The Fire Ryzens

The story of AMD is like the story of David and Goliath. Except there are two Goliaths.

Intel invested over $12 billion in research and development last year. Most of it was likely spread among general technologies, from which they make no profit, but at least some of that was for CPUs. Nvidia spent $1.46 billion last year, which is $400 million more than AMD.

For years, AMD was given the “wait and see” approach. They were releasing processors with underwhelming performances compared to other options, and that were not as efficient, so they ran hotter. Intel and Nvidia had gained headway in their respective industries and secured their first place positions for the time being.

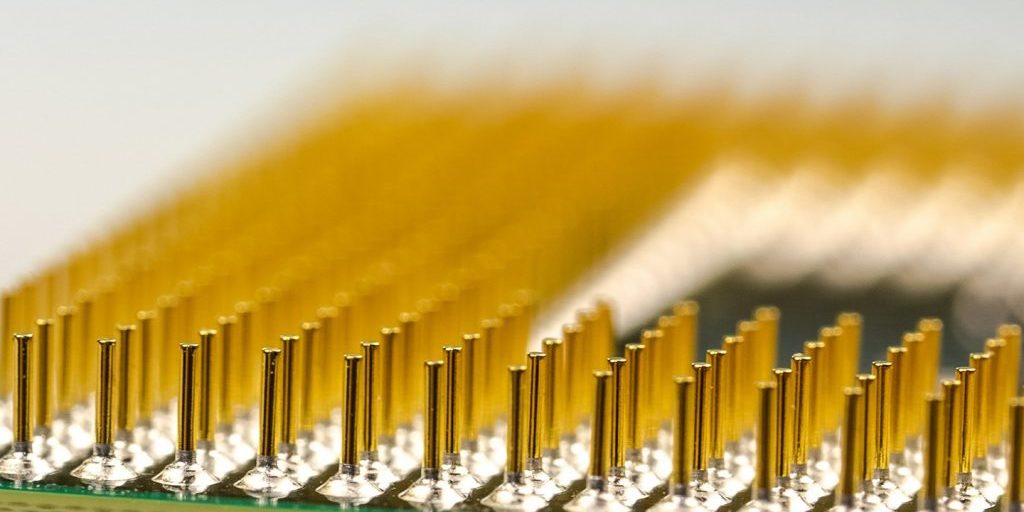

In February 2017, AMD introduced the world to Ryzen. The new processor was a complete departure from the previous generations of chips. It featured a 14nm FinFET build process, power efficient “system on a chip” design and a completely new microarchitecture dubbed Zen.

“This is the first time in a very long time,” says Zen team leader Suzanne Plummer “that we engineers have been given the total freedom to build a processor from scratch.” Not only are they beating previous performance scores, they are giving Intel some second thoughts.

The first Ryzen chips were targeted for mainstream and performance users. On the low end, the Ryzen 5 1400 gave consumers 4 cores, 8 threads, and 3.2GHz clock speed for a paltry $169. Power will find the Ryzen 7 1800X more appealing with its 8 cores and 16 threads for $499. The Ryzen sets itself apart with its sheer number of processor cores, allowing it to be twice as fast as its competition for almost half the price.

Where some Intel processors have locked speed multipliers, all Ryzen chips come unlocked, allowing hardware enthusiasts to upgrade to the next tier processor with little effort.

AMD is also gearing up to meet and possibly surpass Nvidia in the consumer video card market with Vega. Details are being kept under wrap, but some information indicates that the new cards will easily compete with Nvidia’s top tier performance 1080 series.

Apple is also jumping on the Vega train with its brand new iMac Pro. With 5K retina display, up to 128GB of DDR4 memory, and an 8GB or 16GB Vega card, this will be the most powered Apple computer for years to come.

AMD is not rushing its state of the art video card out the door. Its cards, which most consumers might be able to afford, were launched last November. The RX series was a step down from the previous model by replacing or removing several expensive components and drawing less power. The RX 480 ended up being slightly slower but retailed for 1/3rd of the retail price of its predecessor.

The RX 480/580 cards were seen as an incredible value for their price and their popularity rose exponentially after it was learned that they mint money.

Gold Rush

“Out of Stock” is the message you are going to find across various retailers if you try to buy a new RX 480 or 580 (identical except for a 5 percent difference in performance for 5 percent more money). About 6 months after the card’s release, supplies ran out almost everywhere. You might find a new or used one on eBay, but be prepared to pay double.

Why the sudden popularity? The Polaris architecture is efficient at generating cryptocurrency. Just one card is capable of mining $3 to $4 per day (before electricity costs), and a determined miner could fit 5 cards in a single system. Miners bought out every online store and scored bulk quantity orders directly from the manufacturer.

Not everyone who managed to snag an RX card uses them for financial gain. The Folding@home project is a distributed computing initiative by Stanford University. While your computer is idle, it downloads and crunches various tasks for disease research. While it may be awhile before you might get your hands on a new model video card, but at least people who do have them are using them for good.

LATEST STORIES