Could Auto Injury Law be a Casualty of Self-Driving Cars?

BY Ryan Conley

LISTEN

Autonomous vehicles, or self-driving vehicles, are in the news every day. Google has captured the public's imagination with extensive successful testing of autonomous cars on public roads. But they're not alone: virtually every major car maker has limited automated features available on some models. Many executives are on record as forecasting the availability of cars that can largely drive themselves in the early 2020s.

Autonomous vehicles have the potential to change cities and lives just as much as the automobile did throughout the first half of the 20th century. The most striking benefit is the potential for saved lives. In the US alone, over 32,000 people died in auto accidents in 2014. Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla Motors, predicts autonomous vehicles will be ten times safer than human-driven cars by 2022.

It's fair to say some guesswork likely went into that number because the technology is rapidly advancing and the challenges toward total autonomy remain great. But it's likely the public will demand autonomous cars consistently demonstrate extraordinary safety before they'll put up with driving next to them on the highway. Until they can do that, they simply will not come to market.

In recent monthss, Tesla received a great deal of negative publicity over the revelation that its “Autopilot” feature failed to prevent a fatal crash in Florida in May. A man driving on a divided US highway was killed when a tractor trailer turned in front of his car. According to Tesla, the vehicle’s sensors failed to register the side of the white truck against a brightly lit sky. Neither the vehicle nor the driver applied the brakes before the car collided with the trailer at 65 mph. Another crash, in Montana, occurred on an undivided highway, contrary to Tesla’s explicit warnings, and a third, in Pennsylvania, was found not to involve Autopilot. But the string of bad news nevertheless dealt a blow to the automaker. Consumer Reports went as far as to call on Tesla to disable Autopilot for the time being.

Both these crashes and the publicity around them are inevitable. No autonomous feature will ever be perfect in the sense that it can avoid every possible collision. Whatever collisions occur, no matter how infrequent, will be newsworthy, and the coverage will often lack context. The context for the one confirmed Autopilot-related fatality is that it occurred after some 130 million total miles of driving with Autopilot engaged. The worldwide rate of auto fatalities in all cars is one per 60 million miles driven.

As tragic as the fatal Florida accident is, it will help Tesla engineers understand their product’s shortcomings and improve upon them. There is a good chance that updates to the system will be entirely software-based, allowing Tesla drivers everywhere to benefit from improved accident avoidance with a simple, automatic software update.

In the meantime, automakers continue to push forward with self-driving features. Some companies believe the way to develop autonomous technology is an incremental approach. Simple features like cruise control and antilock brakes are nearly universal. More advanced features like distance-keeping cruise control, automatic parallel parking, and automatic braking to avoid frontal collisions are available in pricey cars and beginning to appear in downmarket vehicles as well. More recently, advanced features such as highway lane-keeping have been introduced in select vehicles. The incremental approach says this is the way to go: gradually take over certain responsibilities from the human driver, like tedious highway driving and split-second accident avoidance, but keep the driver involved and ultimately responsible for anything that could go wrong.

Auto manufacturers can hardly be blamed for this line of reasoning. Assuming responsibility for traffic collisions is a nightmare scenario for them. If the technology is seen as augmenting a human driver, it is easier to maintain the status quo whereby humans are responsible for the vast majority of collisions.

Google, on the other hand, is expressly not interested in becoming a car manufacturer. The company merely wants to develop and license the technology. It therefore can afford the luxury of approaching the problem in an entirely different way. Google believes that asking humans to maintain responsibility for the safety of a vehicle that is partially autonomous is unrealistic. After all, even drivers who are ostensibly in total control of their vehicles routinely become distracted to the point of rear-ending another car simply because they're looking at the radio or their phone.

Researchers have tested how long it takes a driver, starting from a highly distracted state wherein the car is behaving autonomously, to refocus on his surroundings, assess the circumstances, decide on a course of action, take control of the vehicle, and safely maneuver it. The sequence can take three seconds or more—far longer than a typical window for avoidance of an imminent hazard that is beyond the capabilities of a partially autonomous car's computers.

The approach being taken by Google and others, therefore, is to work toward the total removal of human drivers from the equation. On public roads, the company operates test vehicles with full controls for both the computer and the human driver. When all goes according to plan, the driver need never touch the wheel or pedals. On private test tracks, Google is testing a vehicle that takes the concept much further: a small two-seater that has one single human control: a big red emergency stop button.

Refreshingly, state and federal regulators seem to be accepting of the reality of autonomous cars and prepared to allow testing, at least. In most states, laws have no provisions whatsoever for the vehicles, and so they are in a legal gray area. In others, testing of SDCs occupied by licensed human drivers as a fail-safe is expressly permitted. The NHTSA, in response to a request for clarification from Google, recently told the company it would consider autonomous driving systems a “driver” of a vehicle for purposes of its own regulations.

Polls indicate widespread interest and at least cautious acceptance by a majority of the American public toward the technology, provided it is proven safe. A 2012 political television ad ahead of a state house primary vote in Florida was meant to put a scare into voters about driverless cars. The ad, which featured an unoccupied vehicle blowing through a stop sign in front of an elderly pedestrian, attacked State Representative Jeff Brandes for his support of autonomous vehicle testing on public roads. Floridians didn't take the bait, and Brandes was reelected.

Clearly, regulators and the public do not appear, by and large, to represent great obstacles to the advent of autonomous vehicles. And while significant technological hurdles remain, including operation in rain, snow, on roads under construction, and at intersections controlled by police using hand signals, the astounding pace of development indicates any delays caused by these challenges will not last long. Ten years ago, few people had ever heard of autonomous cars. Today, self-driving cars from Google alone have logged over a million miles with minor accidents in the single digits.

There can be little doubt that attorneys in practice today will live to see the day when autonomous vehicles are less error-prone than even the safest human drivers, no matter the road conditions. It's important to recognize the likelihood that the technology will result in a huge reduction in traffic accidents, severely impacting the ability for attorneys and insurers to make a living based on them.

The time frame for this phenomenon is difficult to predict, but if autonomous vehicles start hitting the road in large numbers in the early 2020s, they're likely to have a measurable, and perhaps dramatic, impact by the late 2020s. Auto injury law could be an industry in steep decline in 10 to 15 years.

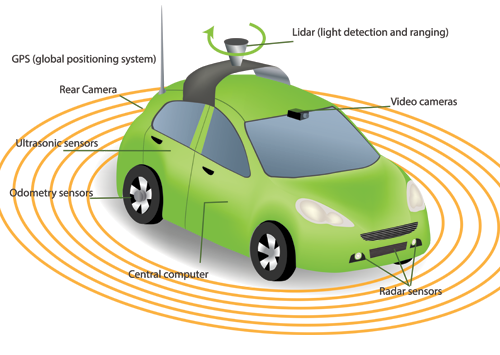

Another factor for personal injury lawyers is the increase in transparency that self-driving cars will impart on collisions. Autonomous vehicles are data-gathering machines. In order to perform safely, the computers on board must know as much as possible about the location, speed, and orientation not just of their own vehicles, but of other vehicles and pedestrians. These data will be measured many times per second and securely recorded, making it easy to determine the exact cause of the accident in most cases. When blame can be reliably pinpointed, the need for litigating gray areas may decrease.

But it's not all bad news for attorneys. After all, every product has flaws, and brand new products running on countless lines of computer code are certainly no exception. Just as human drivers are error-prone, so too are designers of autonomous vehicles. Vehicle software will inevitably contain shortcomings and errors. Even as auto collisions decline, new opportunities for product liability litigation may open. Design defects, manufacturing defects, and breach of warranty are all fair game.

The legal responsibility for safe operation of a vehicle could shift from a single driver to a host of third parties: component manufacturers, software companies, programmers, mapping companies, and others will play a role in developing cars that avoid accidents. The litigation landscape will gradually shift from countless incidents with very few parties per incident to fewer incidents overall, but involving many parties.

Some of these parties will have very deep pockets. And in cases where an autonomous vehicle does in fact cause a collision, the reams of data generated and recorded will make liability more difficult to obfuscate. This will diminish the advantages bestowed on large companies by their immense legal budgets. If and when a company's product causes an accident, it will be difficult to hide, and they will be desperate to settle. They cannot afford the publicity or uncertainty of a trial.

Fewer incidents. More defendants. Potentially greater damages. Likely less litigation. Together, these factors add up to less work for fewer attorneys, but perhaps greater rewards. The downside, of course, is that those who choose to pursue these cases will be in uncharted waters. Literally and figuratively, the rules will be rewritten for all parties involved.

LATEST STORIES