The Digital Arms Race: Apple, the FBI and a Law Against Secrets

BY Ryan Conley

LISTEN

On December 2, 2015, husband and wife Syed Rizwan Farook and Tashfeen Malik opened fire on Farook’s co-workers at a training event and holiday party for the San Bernardino County Health Department. Fourteen were killed and 22 were seriously injured in what the White House called an act of terrorism.

After Farook and Malik were killed in a shootout with police later that day, the FBI searched the couple’s Redlands, California home and discovered Farook’s employer-issued iPhone 5C. Digital forensics analysts soon realized that the agency’s best hope of unlocking the phone may have died along with the couple. A potentially pivotal source of evidence in one of the highest-profile crimes in recent history might prove utterly impenetrable to the nation’s top investigators.

Apple, when presented with a warrant, has frequently assisted law enforcement in accessing certain data on older versions of its iPhone operating system. But newer versions, including the one running on Farook’s device, cannot be compromised in that way. The FBI therefore sought a court order compelling Apple to create custom software bypassing some of the phone’s fundamental security features, and Apple strongly objected.

Apple and the FBI geared up for a major new battle in the long-running fight over the balance between the security of encrypted communication and investigation of crimes. But on March 28, 2016, the FBI announced that it had successfully unlocked Farook’s iPhone, circumventing its security with the help of a party outside the U.S. government. The FBI ended its effort to compel Apple’s assistance, and the battle was called off.

But the greater question of whether companies’ and citizens’ use of and access to strong cryptography will eventually be curtailed by the courts or by Congress still looms.

The Order

Like many modern smartphones, Farook’s iPhone was protected by a four-digit PIN, or passcode, and its contents were encrypted. The number of possible passcodes, at 10,000, does not by itself represent an insurmountable obstacle. But an optional extra security feature on the phone automatically erases its encryption key if ten incorrect passcodes are entered, rendering the phone’s contents permanently inaccessible. Investigators could not determine whether the feature was enabled, but could not run the risk of destroying their chances of unlocking the phone.

On February 16, 2016, U.S. Magistrate Judge Sheri Pym ordered Apple to help the FBI unlock and decrypt the iPhone. The assistance would come in the form of the creation of new software for the phone, which would disable the auto-erase function, allowing the FBI to “brute force” the passcode. In other words, they would simply enter every possible PIN in succession until they happened upon the right one — a task they could accomplish in minutes with the aid of computers.

The FBI probably could, in fact, create its own custom software that would allow a brute-force attack on the iPhone’s passcode. What it can’t do is install and run that software on any iPhone. Like many other devices, iPhones will only accept software containing a secret digital signature known only to the manufacturer.

In its filing requesting the order, the government invoked the All Writs Act of 1789, a catchall statute that allows courts to issue orders compelling individuals or companies to perform some action. Apple says this application of the Act is “unprecedented” in that it would force them to remove vital features of their product. The company says no other government has asked it to do what was being requested in this case — not even Russia or China.

Apple closes a loophole

Apple increased security significantly with the introduction of iOS 8, which included upgrades that kept all of the user’s sensitive data under the encryption umbrella. The phone must be unlocked with the correct passcode in order to access any user data.

Apple was not shy in pointing out the implications of beefing up the encryption. With the introduction of iOS 8, the company said on its website, “it’s not technically feasible for us to respond to government warrants for the extraction of this data from devices in their possession.” That’s why the government argued they must turn to this new strategy of compelling Apple, via the All Writs Act, to create custom software that enables brute force discovery of passcodes.

False hopes, false fears

It seems unlikely for two reasons that Farook’s iPhone contains any data valuable to the investigation. First, Farook and Malik went to the trouble of destroying two other phones beyond the point where forensic analysts can recover any data from them. They also removed their home computer’s hard drive, which investigators have been unable to find. They left the iPhone in question at their home during the attack, so it presumably played no logistical role in the attack itself.

Second, the phone was issued to Farook by his employer, which retained ownership of the device as well as control over the phone’s account on iCloud, an Apple data-backup service. The phone’s contents were not backed up to iCloud for a period of six weeks leading up to the attack — a lapse that could indicate either an attempt by Farook to hide information, or an ordinary lack of data diligence. Nevertheless, the employer’s control over iCloud accounts for company devices was common knowledge among employees. For Farook to elect to conduct incriminating activities on this phone instead of his personally owned and controlled devices, which he took pains to destroy, is difficult to imagine.

If the FBI’s professed hopes for finding valuable clues on the iPhone are dubious, Apple’s argument in resisting Judge Pym’s order is perhaps even more so. In an open letter to Apple’s customers, CEO Tim Cook claimed that the software circumventing the iPhone’s security features “would have the potential to unlock any iPhone in someone’s physical possession.” But the order explicitly required the newly-created software to be uniquely tied to Farook’s iPhone. This would be accomplished by incorporating references to unique identifying codes present in certain components, such as the cellular and Wi-Fi radios. If someone then tried to install the software on another iPhone with different components, the process should fail.

Furthermore, the FBI was not seeking to have Apple hand over the software they create. The court order allows for the iPhone to remain in Apple’s possession while they install the custom software, with the FBI having remote access to the device. Under those circumstances, it seems, at first glance, very unlikely that the software could end up in the wrong hands, as Cook claims he fears.

In the court of public opinion, both the FBI and Apple are appealing to fear rather than reason. The government wants the public to believe that terrorists can only be stopped with assistance in bypassing or hobbling smartphone security features. And Apple would have us believe that the custom software they may end up creating would amount to a backdoor into anyone’s data at any time.

It’s the precedent that matters

Superficially, neither party’s argument is compelling. Nevertheless, the aborted legal battle would have had huge consequences in the precedent it set. Cyrus Vance, Jr., a district attorney in New York City, is on a mission to bring attention to the roadblock that phone encryption represents to law enforcement. He says his office’s evidence lockers contain more than 150 iPhones running iOS 8 or 9, which they are unable to access. If the FBI had followed through and prevailed against Apple in court, state and local prosecutors around the country would no doubt have filed a flurry of motions requesting custom software from Apple under that legal precedent.

The extent to which the hack on Farook’s iPhone can be applied to other devices remains to be seen, and the public, and even Apple, may remain in the dark on that matter. But it’s safe to say this outcome represents a lesser victory for law enforcement than would a precedent for compelling Apple to do the heavy lifting.

In his letter to customers, Tim Cook said an FBI legal victory would create a slippery slope of increasingly underhanded surveillance of its customers. If the company must compromise its own security features, Cook says, later orders could force them to “build surveillance software to intercept your messages, access your health records or financial data, track your location, or even access your phone’s microphone or camera without your knowledge.”

Are Apple’s fears warranted?

While Apple may be overselling the immediate danger of creating custom software for the FBI, more subtle legal issues may in fact justify such concerns. In a February 18 blog post, Jonathan Zdziarski, an expert on iOS forensics, draws a stark contrast between services that Apple has rendered to law enforcement in the past — i.e., a simple copy of certain unencrypted data — and the software it is being asked to create for the FBI. The former, Zdziarski says, is a lab service, the exact methods of which are not subject to great scrutiny because they constitute trade secrets. The latter, on the other hand, is a forensics tool — an instrument. As such, it is subject to far stricter evidentiary standards.

An instrument used by law enforcement to carry out a method of investigation must be rigorously proven to produce replicable results. It must be validated by a third party such as NIST, the National Institute of Standards and Technology. It also must be made available to defense attorneys who want independent third parties to verify its accuracy. Zdziarski points out that these are all potential points of failure where the software could end up in the hands of criminal hackers or oppressive governments who might be able to use it for their own illegal purposes in spite of Apple’s safeguards.

These concerns may have lain dormant in the Farook case, as both the suspects were already dead; there is no defense attorney to object to the reliability of any evidence discovered on the iPhone. But if a government agency successfully prosecutes the custom-software strategy in some future case against Apple, and other prosecutors seize upon that precedent, it’s easy to imagine a worrying number of people gaining intimate knowledge of the software’s inner workings. Apple’s fears of opening Pandora’s box may be well founded after all.

A dystopian future?

On March 21, just one day before a scheduled hearing on whether Apple would have to assist the FBI, the agency asked to delay the proceedings. A third party had demonstrated a technique that might allow them to break into Farook’s iPhone. One week later, the agency dropped its case, claiming the method was successful.

However, the broader dilemma remains unresolved. No third-party method for breaking into a given device can be assumed to work with other devices and operating systems, both present and future. And Apple seems committed to creating products impenetrable not only to governments, but also to the company itself, having already eliminated the technical loophole by which certain data remained unencrypted. If Apple is ever compelled to devise a way to bypass its best security features, it could then go to work making its security even better, fortifying its devices and software against exactly the vulnerabilities that allow such exploits.

The prospect of a perpetual cryptographic arms race between law enforcement and high tech companies can make an intervention by Congress seem attractive by comparison. Many legislators and top law enforcement officials have advocated for years for a legislative solution mandating a “backdoor” into all cryptographic devices and software. The backdoor would ostensibly be accessible only to the U.S. government, and only with a warrant, but civil liberties advocates have doubts as to whether those goals of secrecy and legal diligence could be met.

Even if companies could create backdoors accessible only to the U.S. government and only in cases of serious crimes, experts allege creating it would in fact be a fool’s errand, transforming the government’s digital arms race against tech companies into a war against the entire tech industry, its own citizens and the very concept of secrecy.

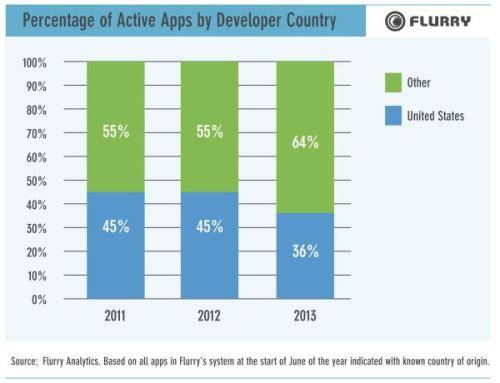

Suppose Congress required a backdoor to be built into every device and application made in the United States. Many smartphone applications are created in foreign countries.

Would the government compel Apple, Google and others to exclude foreign encryption software from their app stores? What about applications loaded from unofficial app repositories? Would companies be required to monitor every user’s smartphone for evidence of illegal cryptographic apps obtained through such repositories?

And if, at great expense and effort, even those apps were somehow kept off Americans’ phones, determined customers would turn to web-based cryptographic software already available. Following this hypothetical scenario to its logical end, it becomes clear that if the U.S. Congress wishes to keep all non-sanctioned cryptographic software out of the hands of everyone in its purview, the government must monitor and censor all domestic internet traffic — we must become China.

Politically, such an outcome is utterly infeasible. But that does not doom us to a world where electronic evidence can never be uncovered. Numerous uncontroversial avenues for evidence collection remain available for law enforcement. Phone calls, emails and texts tend not to be encrypted, and user data and even encryption keys themselves are often backed up to vendor-controlled servers by default. In cases where police apprehend suspects, biometric login data such as facial or fingerprint scans are easily obtained, and suspects may even be compelled to give up passwords or PINs without violating the Fifth Amendment in some cases. Suspects savvy enough to avoid every weak link in digital security will remain a thorn in the government’s side, but those are exactly the sort of people for whom a government crackdown on encryption software would be a non-issue.

Some are so fearful of a world where digital secrets remain secret that they would steer us down a dark road toward a point where surveillance is so pervasive as to eliminate any semblance of privacy. But long before we get to that point, we will realize that the road is far too dangerous, and we have far too much to lose by continuing along it. With privacy advocates, the tech industry and principled lawmakers leading the way, people will make the courageous choice to forge a new and better path.

LATEST STORIES